The teaching of Anaxagoras ends the first stage of the history of philosophy: the stage of unconscious philosophy. What is unconsciousness?

All the philosophers who spoke at this stage thought about the origin, but none of them considered the origin of thinking itself - the mind.

The principles were very different: water, number, being, identical to thinking, but not thinking, but only thinkable. Even for Heraclitus, logos is not a thinking thought, it is elemental.

“Not for me, but by listening to the logos, it is wise to recognize that everything is one”

And only with Anaxagoras did thinking appear as the primary principle. Anaxagoras, unlike Democritus, understood that matter itself will not form as it should, this requires goal-setting thinking. Homeomerism is matter, nous is the mind that organizes it.

At the same time, the person himself turned out to be, in a sense, involved in the beginning. Man, thanks to his mind, is the master of things. Since all things are created by the mind, they can be handled wisely. Imagine if water was not defined in relation to other elements - fire, for example. If she was extinguishing the fire, then no. Fortunately for the firefighters, the water is certain, for which they have their minds to thank.

Anaxagoras completes the spontaneous, unconscious, naive thinking of the first philosophers (naturally, this was not naive, non-philosophical “grandmother’s” thinking). The subject of investigation has become the mind, and unconscious investigation of the mind is impossible. The conscious thinking of philosophers begins with Anaxagoras. About what? About the rational cause of everything that exists, for this is the new subject of philosophy.

It seems that interest in nature disappears, and the anthropological period begins, as they say in philosophy textbooks. This opinion is not right, because it only captures the negative moment of the transition to a new form of objectivity.

So, the subject of philosophy becomes the mind, and its closest “carrier” is man. If a person is independent, then he is smart, but if his life is determined by something else - tradition or chance, then he still needs to grow to intelligence. What did the Greeks usually do? They acted either on the basis of tradition - “this is what our fathers and grandfathers did,” and in some cases, when tradition did not prompt, the Greek went to the oracle or cast lots. Those. they did not live by their wits. And when they had a need for independence, the sophists appeared.

The emergence of the Sophists

The Sophists arose due to the fact that a turning point occurred in the spirit of the Greek people - the Greeks felt the need to be guided in actions and deeds by their own mind. The Greeks have grown to their senses. This apparently made it easier for Anaxagoras to discover that some have intelligence.

In IF one should forget about the bad interpretation of the sophists. The uneducated public has the opinion that a sophist is an insidious demagogue who confuses a naive but good person with his speeches. As soon as such an audience notices that a person can look at an object this way or that way, it becomes frightened, sensing danger. The opportunity to know about something that it is both like this and not like this, causes a protest in a good fellow: “They are confusing me, for some reason they want to fool me!” The people who fear being fooled the most are idiots. You can't fool a fool.

Sophists are teachers of wisdom (that's what they called themselves). These are people who are wise themselves and can make others wise and strong in speech. They taught people to reason independently and express their thoughts convincingly. Real wisdom is not much knowledge like: I know where Africa is, where the Volga flows, etc.

The Sophists would not have arisen if the Greek people in the era of Pericles had not felt the need for self-determination, if the conviction had not arisen that a person should not be determined either by tradition, or by momentary passions, or by chance. People realized that in order to become independent, they need to process what is alien to them (that is, spontaneously formed ideas that they simply accepted and did not form on their own) and make them truly their own. The Greeks understood that their own thought must rework their own spontaneously formed opinions. On the basis of this, there was a revolution in the way of thinking, which was started by the Sophists.

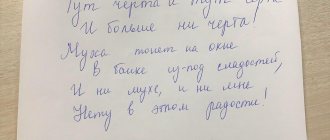

How good our people lived when people thought for them. This is not only in the era of the CPSU, but also the hope in the Tsar-Father, the eternal Russian: “The master will come, the master will judge us.” Many also love the army precisely for this reason, where the essence is submission without thought. By definition, a soldier in the army cannot know better than the commander - the laf!

Now the Russian people are maturing to the idea of self-government (self-determination), the people want to learn to think independently. We are now in the same position as the Greeks in the era of Pericles (IV century BC) - therefore it is useful for us to study the sophists.

The Greeks wanted to determine their own lives, but if they are crazy, then there is only one thing left - to obey individual momentary passions. But it's not reliable. There was a need for competent answers to life's questions. The sophists were the first paid teachers who taught people to reason. How was the Greek formed before this? Spontaneously, through poems.

Since the need for education of the mind was high, some sophists lived luxuriously. Not only young people were interested in sophistry, but also politics. The strength of a politician lies in his ability to persuade. The tyrant does not need this skill: they do not agree - “axe head” - and there are no dissenters. An eloquent politician speaks convincingly. The art of a popular politician is to be able to present his interests as the interests of the people, to convince the people to follow him, as a representative and spokesman for the people's interests.

But the sophists contributed not only to the education of the Greek people - among them there were also those who contributed to the history of the development of philosophy. Such are Protagoras and Gorgias.

Elder

Sophists, as a phenomenon in the history of thought, are usually divided into two groups. The first is the so-called “elders”. These include all the main achievements attributed to this philosophical direction. The "Elders" were contemporaries of many other great sages. They lived during the time of the Pythagorean Philolaus, representatives of the Eleatic school Zeno and Melissa, natural philosophers Empedocles, Anaxagoras and Leucippus. They were more of a set of techniques, rather than some single school or trend. If you try to characterize them as a whole, you can see that they are the heirs of naturalists, since they try to explain everything that exists by rational reasons, point out the relativity of all things, concepts and phenomena, and also question the foundations of contemporary morality. The philosophy of the older generation of sophists was developed by Protagoras, Gorgias, Hippias, Prodicus, Antiphon and Xeniades. We will try to tell you more about the most interesting things.

Protagoras

He was the first to call himself a sophist. Spoke with Pericles. Like Anaxagoras, he was expelled from the city. He was expelled for writing “On the Gods.” This book is the first to be destroyed at the behest of the state. There were these lines:

“I cannot know anything about the gods, whether they exist or not: this is hampered by the darkness of the subject and the brevity of human life.”

“Why do you, Protagoras, want to know the gods with your mind? - asked the Athenians - “We must do the same as everyone else.” It is clear that this could not be allowed to happen.

Next we will consider the philosophical in the sophistic teaching of Protagoras. He succeeded Zeno of Elea and Heraclitus. The actual basis for sophistry is there: “Everything flows.” But the sophists have their own conclusion: “Since everything flows, then it can therefore be everything that it seems to someone.” Since everything flows, do we know what it is like in itself? No, and, therefore, it is what it is for us. People's feelings are changeable and the same person perceives everything differently. What's the wind like? Neither cold nor warm, but such, Protagoras would say, as he is perceived. A sick person finds food bitter, a healthy person finds it sweet. So what is it like in itself? Just as it seems.

No thing should be spoken of as it is in itself. She is what anyone perceives her to be. It is such because it is in relation to man. Nothing is one thing in itself, but everything is in relation to another and only in this way, according to Protagoras, can it be assessed. And, therefore, all opinions are equal; none of them can be said to be false. You cannot argue with a person who is cold in the wind, even if the wind seems warm to us.

Hence the principle of Protagoras’ teaching:

“Man is the measure of all things: those that exist, that they exist, and those that do not exist, that they do not exist.”

And if something doesn’t exist for someone, then it doesn’t exist (for him). Consequently, the existence and non-existence of things is in the power of man. No one can determine for the person himself what this or that thing is for him. “You know, this thing is like that for you,” we say to each other. “Sorry, I know what it’s like for me.”

The Protagoras principle is the first formulation of human freedom.

Why is man a measure?

Because he realized himself as a thinking being. You cannot be a thinking being without knowing that you are the measure of all things. In relation to finite things, man is absolutely free. What is behind the Protagoras principle? One: awareness of the absolute power of the human mind over individual things. Anaxagoras paved the way for him: “The mind rules the world.” The small mind rules the human world - the world to which a person belongs. The human mind is the measure of everything individual.

Educating the human understanding so that it can handle things freely is the principle of the Sophists. An educated mind knows that it can do anything with things. An uneducated mind does not know that it can do everything with things, and therefore cannot do everything. Let us emphasize: reason has absolutely omnipotent power over individual things, and not absolutely power in general. Why is the educated mind omnipotent? Because he has power over himself, but the uneducated has no power over himself, he is spontaneous. Why is he omnipotent over individual things, and not in general, because to control oneself for an educated mind means to control one’s own attitude towards individual things; no one can indicate to an educated mind exactly how it should treat a thing, no one can determine for it what it is for him.

How does reason command?

The mind can do whatever it wants with its ideas about things. For example, the idea of a glass. What is a glass? The uneducated mind knows that this is a drinking device. He has the experience that you can drink from a glass, that the glass allows you to do this with him. An educated mind knows what it can do with a glass - everything that it imagines about it: throwing, covering flies, turning the glass into a zoo - you watch and have fun. It can also be used as an investment: an antique glass is a great gift for a friend.

How many actions can the mind perform with a glass in its mind? Infinite quantity. Reason can decompose the one into many. The certainty of my idea depends on someone. From no one! Sophistic teachers of rational thinking raised reason from a state of spontaneous, naive thinking to an educated state. It’s one thing to be a slave to things, and another to be a master. But so do people. You can decompose any idea into many ideas, highlight those aspects of it that are important to you and convince others of this. What's opening here? The danger of arbitrariness: what I need, I will allocate; there is a danger of presenting one’s goals as the universal, the partial as the whole.

Nowadays, all more or less educated people are their own sophists. Whether or not to go to class in the morning is our decision (although, of course, there are those who do it automatically). I wonder what? The fact that whether our decision is “for” or “against”, it can be well justified by us! That is, reason can justify what is important for us as necessary in general. Why is this possible? Because reason gives finite definitions, and their “infinite” number, therefore, can be chosen to suit your taste. In this rational way, you can justify anything. This is the dangerous side of an educated mind.

An uneducated person under the rule of tradition is constant. And education opens up scope for arbitrariness. That’s why rulers hinder education—it’s easier to govern, and you don’t even need to govern—tradition, the status quo, governs for them. The Sophists showed that there is something in a person that allows him to be free. But since this freedom is rational, this freedom is arbitrariness. This is the great danger of education. Greek society felt that there was danger here, because... Greek society was a traditional society. Man has become able to live by his own mind, and, therefore, independently of others: the unity of the state and society is destroyed.

And from a philosophical point of view, it was generally a scandal. Philosophers spoke about true knowledge and opinion, but now it is over: every opinion is true as long as a person adheres to it. If you don’t like it, you’ll choose a different point of view and justify it.

Absolute truth has disappeared!

They say: “Humanity needs to seek the truth.” “Come on, an educated person does not need to seek the truth,” say the sophists. Truth appeared as something relative. Opinion turned out to be the most important. What kind of divine logos there is - this is only the opinion of Heraclitus. Form your mind, and your opinion will become absolutely equivalent to any other opinion. It began to seem that a person was not given anything more than to come up with opinions. Philosophy became popular - everyone could philosophize from the heart. "What is truth?" “Something united,” they said earlier. “Come on, does she exist?” - the educated sophist waves his hand.

Any relativism is based on sophistical thinking. It is precisely from the realization that anything can be proven by rational means that the opinion arises that nothing definite can be known. There are reasons to steal and there are reasons not to steal. What is important to me, I decide for myself. Terrible danger. If there is no absolute truth, then everything is permitted. If truth is relative, then it is impossible to know anything at all. Gorgias justified this.

About religion

The Sophists were known for ridiculing and criticizing belief in the gods. Protagoras, as mentioned above, did not know whether higher powers really existed. “This question is unclear to me,” he wrote, “and human life is not enough to fully investigate it.” And the representative of the “younger” generation of sophists, Critias, received the nickname of the atheist. In his work “Sisyphus,” he declares every religion a fiction, which is used by cunning people to impose their laws on fools. Morality is not at all established by the gods, but is fixed by people. If a person knows that no one is watching him, he easily violates all established norms. The philosophy of the Sophists and Socrates, who also criticized social mores and religion, was often perceived by the less educated public as one and the same. No wonder Aristophanes wrote a comedy in which he ridiculed the teacher Plato, attributing to him unusual views.

Gorgias

He buried absolute truth. “About that which does not exist or about nature” is a mockingly titled book (after all, previously almost all philosophers wrote books “About nature”).

Aristotle conveys the provisions of Gorgias:

- There is nothing.

- If there is, it is not knowable.

- Even if it is knowable, it is incommunicable to others.

Proof:

We can say that non-existence exists (Heraclitus). This means that there is something that is not there. But this is a contradiction, from which it follows that there is nothing: neither existence nor non-existence, but there is only an opinion about them.

But even if it is proven that something exists independently of our thinking, then it is not knowable, because from the way it seems to me, it does not follow that it is such in itself. Our reason cannot give us knowledge that there is a thing itself apart from its relation to it.

And the last nail in the coffin of truth: words are not thoughts, but only words, therefore it is impossible to convey any thoughts with their help.

Sophistry - a direction of philosophical thought

Sophistry, as a multifaceted way of thinking, acquired a complete form at the end of the 5th century BC, becoming a subjective idealistic philosophical direction - sophism. Now sophistry has a completely different concept - intellectual fraud. In antiquity, it was associated with special wisdom, the ability to convey scientific knowledge for money. Representatives of the movement were excellent teachers, early scientists, and professors. Philosophers called themselves sophists. Their appearance led to the birth of the Sophia school.

Results

The conclusions of the sophists are not sophistry. These conclusions are true about this thinking - about reason. If our thinking is only rational, then everything that Gorgias said is true: if thinking is truly separated from the object, then such thinking cannot know anything about the object in itself. Reason knows that it is the master of things, but it does not yet know why it is the master. He is pleased with this find and happily amuses himself with it.

Reason contradicts itself. Reason itself does not go beyond the boundaries of opinion, but within these boundaries it is free. A person with an educated mind is one who can prove both of the same things. The moment of truth for the sophists is the awareness of the power and powerlessness of reason: absolute power over individual things and powerlessness before the truth. He is so powerless that he declares that there is no truth. The question is: does he claim the truth? Yes, there is no truth, but only as an individual thing located outside of us. What if truth is not a thing?

The own contradictions of the sophistic way of thinking became the starting point for Socrates' philosophizing.

Type of activity of the Sofia school

Schools of oratory were first mentioned in the 5th century in Sicily. But it was Athens that became the public arena for the educational activities of the Sophists. The doctrine touched upon the epistemological problem of philosophy. Adherents of the ancient school tried to teach followers to refute the conclusions of political opponents with the help of evidence and reasoning. In this endeavor, they encountered socio-political problems, for the sake of solving which they dealt with general questions of truth and falsity. It follows from this that philosophy, represented by the teachings of the Sophists, is an important direction in the science of thought in general.

Leading a traveling lifestyle, the sophists performed in front of everyone who wanted to learn eloquence. They “toured” cities, using pedagogical rhetoric to unite groups of people differing in age, gender, and social status. The sages made a huge contribution to the development of society - they cultivated an understanding of the importance of not only physical and spiritual education, but also mental education. Education acquired the highest value and became widespread. “An educated person is confident in himself, able to withstand the crowd, strong in thought, his weapon is the word,” thinkers were guided by this motto.

Due to their “wandering” lifestyle, the Sophists did not have a developed system of knowledge. The manuscripts have not survived to our time; we can study sophiology only on the basis of the works of philosophers of the late period.

Prodicus's interest in language

The Sophists studied the theory of words a lot, so they can be considered the first Greek philologists. Prodicus especially delved into verbal semantics.

Prodicus of Keos (c. 470 - after 400 BC) was a Greek sophist. In 431 or 421 BC. e. received great acclaim in Athens. He developed Protagoras' doctrine of correct speech. Prodicus dealt with synonymy, emphasizing the differences between words with similar lexical meanings. The only works of Prodicus that are reliably known are the Seasons, whose name he associated with the goddesses of the seasons who were worshiped on Keos.

The philosopher-sophist argued: the emergence of agriculture led to the development of human culture. He presented a theory of the origin of religion. Protagoras proclaimed a theory of divine honors for things useful to people (a kind of fetishism) and their inventors (a theory later called euphemerism. A rationalistic interpretation of myths, often named after Euphemer of Sicily Messina (more likely) or Peloponnesian IV/III, Greek writer. Author of the work Sacred Inscription. He was the first to explain the origin of religion by psychological reasons (feelings of gratitude). His understanding of the gods is original. According to Prodicus, the gods are nothing more than a hypostasis. Hypostasis - (from the Greek. Hypostasis - essence, substance ) - a logical (semantic) error consisting in objectifying abstract entities, attributing to them real, objective existence. Useful and useful: The ancients invented the gods due to the superiority, redundancy emanating from them: the Sun, the Moon, the Sources of all the forces influencing our life, for example the Nile on the life of the Egyptians.

In ethics, he became famous for his interpretation of sophistic doctrine through the familiar myth of Hercules, who at the crossroads chooses between virtue and vice, where virtue is interpreted as the appropriate means to achieve true benefit and real benefit.

Hippias as one of the representatives of the Greek Enlightenment

Hippias (rrJabt) of Elis (470s - after 399 BC), Greek sophist, younger contemporary of Protagoras. He is considered one of the most erudite and versatile representatives of the Greek Enlightenment.

Hippias paid a lot of attention to rhetoric. The naturalness and fascination of the story were his main strength; he traveled to different cities more than once on large political assignments and always performed successfully. He traveled throughout Greece as a teacher and speaker, thereby making a huge fortune. He took an active part in government affairs, traveled with embassies to Athens, Sparta and other cities, gave public lectures on the genealogies of heroes and local noble families, and on the founding of cities in ancient times. Hippias wrote works on mathematics, astronomy, meteorology, grammar, poetry, music, mythology and history. He worked on the creation of epics, tragedies and dithyrambs. He wrote poetry, songs, various prose and was an expert in rhythm, harmony, spelling and mnemonics. Despite the diversity of his interests, Hippias basically remained a sophist, since he sharply contrasted tyrannical law with supposedly free nature. He taught the science of the nature of legislation, believing that knowledge of nature is necessary for the success of life, that life should be guided by the laws of nature, and not by human institutions. Nature unites people, but the law rather divides them. The law is devalued to the extent that it contradicts nature. A distinction is born between law and natural law, natural and positive law. The natural is eternal, the second is accidental. Thus, the beginning of subsequent desacralization occurs. Desacralization is the devaluation of sacred (sacral) models, religious ideas, ideological guidelines, etc., human laws that require expertise. However, Hippias draws more positive conclusions than negative ones. He finds, for example, that, as a matter of natural law, it makes no sense to separate the citizens of one city from the citizens of another or to discriminate against citizens within the same city.