Wilhelm Wundt

(1832 - 1920) - an outstanding German psychologist and physiologist, who actually became the founder of psychology as such. Wundt introduced into science an objective study of mental phenomena by analogy with other natural sciences, and showed the physiological relationship between the psyche and the brain; However, Wundt combined an objective approach to psychology with introspection, a method that was later recognized as unscientific.

Life story of Wilhelm Wundt

Wilhelm Wundt was born into the family of a Lutheran pastor. From the outside, this family seemed friendly, but later Wundt recalled how strict and sometimes cruel his father could be. Almost all family members were well educated and distinguished themselves in some science, but Wilhelm seemed to them incapable of learning. This confidence was reinforced by the fact that the boy was unable to pass the entrance exams for the first grade of the gymnasium. Subsequently, however, Wilhelm improved his studies and by the age of nineteen was ready to enter university. He chose a career as a doctor.

While studying at the University of Heidelberg, he studied with Professor Gasse and was also his assistant in the women's department of the local hospital. He had to be on duty almost around the clock, almost at night. During one of these shifts, he experienced a state that, in his opinion, resembled mild somnambulism. Wundt became interested in this topic and decided that he no longer wanted to be a doctor. He transferred to the University of Berlin, where he studied with the natural scientist Johann Muller, and then worked there as an assistant to the famous scientist Helmholtz. At this time, for the first time in the world, he began to give his lectures on scientific psychology.

In 1875, he moved to Leipzig, began working at the local university and, with his own money, founded the world's first psychological laboratory. Subsequently, it grew into the Institute of Experimental Psychology. Wundt lived in this city until his death. Here he graduated a huge number of students, many of whom continued his work. His students founded their own psychological laboratories at Columbia University, the University of Pennsylvania and others. It is curious that scientists from the USA and Russia most often showed interest in his psychological research. Bekhterev, Pavlov, V.S. Serebrenikov, as well as the Pole Vladislav Vitvitsky and the Bulgarian Spiridon Kazandzhiev became Wundt’s faithful students and successors of his work.

In his later period, Wundt concentrated on social psychology and the so-called “psychology of peoples,” laying the foundations for these disciplines as well.

The total number of works by Wilhelm Wundt is difficult to calculate, as are all the areas of his interests. He conducted research in the fields of psychology, philosophy, physics, and physiology. Wundt is considered one of the founding fathers of modern psychology, although in recent decades the significance of his work has been noted as low, since science has moved far forward during this time. Throughout his life, Wundt wrote more than 54 thousand pages; we can say that his cherished childhood dream came true - to become a great writer.

Wundt even made some contributions to astronomy. He was the first to propose calling asteroids not only by female names, as was done before. His student Karl Lohnert, who became an astronomer, heeded this advice: he named the asteroid he discovered in 1907 Wundzia in honor of his teacher.

Thorndike: laws of intelligence as learning

What in the European tradition were designated as processes of association soon becomes one of the main directions of American psychology under the name of “learning.”

This direction introduced the explanatory principles of Darwin's teachings into psychology, as a result of which a new understanding of the determination of the behavior of an entire organism and, thereby, all its functions, including mental ones, was established.

Among the new explanatory principles, the following stood out: the probabilistic nature of reactions as the principle of natural selection and the adaptation of the organism to the environment in order to survive in it.

These principles formed the contours of a new deterministic (causal) scheme. The former mechanical determinism gave way to biological determinism. At this turning point in the history of scientific knowledge, the concept of association acquired a special status. Previously, it meant the connection of ideas in consciousness, but now the connection between the movements of the body and the configuration of external stimuli, on adaptation to which the solution of problems vital for the body depends.

Interesting

The association acted as a way of acquiring new actions, and in the terminology that was soon adopted - learning. The first major success in transforming the concept of association came from the experiments of Edward Thorndike (1874-1949) on animals (mainly cats). He used so-called "problem boxes".

An animal placed in a box could leave it and receive feeding only by activating a special device - by pressing a spring, pulling a loop, etc. The animals made many movements, rushed in different directions, scratched the box, etc., until one of the movements accidentally turned out to be successful. “Trial, error and accidental success” was the formula adopted for all types of behavior, both animal and human. Thorndike explained his experiments using several laws of learning. First of all, by the law of exercise (the motor reaction to a situation is associated with this situation in proportion to the frequency, strength and duration of repetition of connections). It was joined by the law of effect, which stated that of several reactions, those that are accompanied by a feeling of satisfaction are most strongly combined with the situation.

Thorndike assumed that the connections between movement and situation correspond to connections in the nervous system (i.e., a physiological mechanism), and connections are reinforced due to feeling (i.e., a subjective state). But neither the physiological nor the psychological components added anything to the “learning curve” drawn by Thorndike independently, where repeated trials were marked on the abscissa, and time spent (in minutes) was marked on the y-axis.

Thorndike's main book was called Animal Intelligence. Study of associative processes in animals" (1898). Associations were thus interpreted as intellectual, and therefore semantic, processes. All previous psychology considered meanings an integral attribute of consciousness. From now on, they turned out to be inherent in bodily behavior.

Before Thorndike, the originality of intellectual processes was considered a consequence of ideas, thoughts, and mental operations (as acts of consciousness). In Thorndike they appeared in the form of motor reactions of the body independent of consciousness.

In earlier times, these reactions belonged to the category of reflexes - mechanical standard responses to external irritation, predetermined by the very structure of the nervous system.

According to Thorndike, these reactions are intellectual, because they are aimed at solving a problem that is impossible to cope with using the available supply of associations. Only the development of new associations, new motor responses to a situation that is unusual for the animal and therefore problematic, allows us to solve the problem.

Interesting

Psychology attributed the consolidation of associations to memory processes. When it came to actions that became automated through repetition, they were called skills.

Thorndike's discoveries were interpreted as laws of skill formation. Meanwhile, he believed that he was exploring intelligence, and therefore the semantic basis of behavior. To the question “Do animals have minds?” a positive response was given. But behind this there was a new understanding of the mind that did not need to appeal to the internal processes of consciousness. By intelligence we meant the body’s development of a “formula” for real actions that would allow it to successfully cope with a problematic situation. Success was achieved by accident. This view captured a new understanding of the determination of life phenomena, which came to psychology with the triumph of Darwinian teaching. It introduced a probabilistic style of thinking. In the organic world, only those who manage, through “trial and error,” to select the most advantageous response to the environment from many possible ones survive.

This style opened up broad prospects for the introduction of statistical methods into psychology.

Wundt's thoughts in psychology

Wilhelm Wundt was perhaps the first to propose studying psychic phenomena from a natural point of view. While studying physiology and studying the structure of the human body, he noticed that the nervous system and brain are closely connected with the so-called “spiritual sphere.” Wundt showed that human consciousness can be broken down into its constituent elements, as is done with substances and bodies in chemistry and physics. However, his predecessors, adherents of empiricism and associationism, tried to decompose consciousness into “atoms of the brain”; Wundt was the first to point out that understanding the constituent elements is only the first step towards understanding psychology. He was more interested in the question of how exactly these elements are combined into one whole, how they function as a single composition and how they change over time.

Wundt called his system “voluntarism” because he believed that the brain’s ability to self-organize is ensured by willpower.

Wundt argued that psychologists should deal primarily with direct experience of consciousness, because indirect experience does not provide insight into exactly how the psyche functions. Thus, when we say that this flower is red, our attention is focused on the flower, which we already know about from previous experience, and not on the direct comprehension of “redness”. Another example: when a person describes how he feels about toothache, it is a direct experience; and when he says: “My teeth hurt,” then this is already a mediated experience.

Direct experience, according to Wundt, is the process of organizing all the elements of consciousness into a single whole, which is carried out by the brain. And these elements can be separated and studied separately.

In accordance with his theory, Wundt created the world's first psychological laboratory. It studied sensations and perceptions, psychophysical phenomena, reaction time, as well as feelings and associations. Wundt himself did not conduct experiments in the laboratory, but entrusted this work to his students. He would go there at the beginning of class, hand out worksheets to students, then come back at the end of class to collect reports of experiments and decide which ones could be published in Philosophical Investigations, a scientific journal also created by Wundt.

They say that an additional impetus for his research into the “elements of consciousness” was the chemical “Table of Periodic Elements” created by Mendeleev. According to some reports, Wundt was going to create the same table for the “elements of consciousness.”

The German scientist also divided psychology into experimental and social. In his opinion, the experimental method can only study primary mental phenomena, while it is not suitable for higher functions (memory, attention, learning, etc.). This concept was subsequently refuted. However, the social psychology created by Wundt continued to develop. His gigantic ten-volume work “Psychology of Nations” was devoted to language, art, mythology, social foundations, morality, laws, and through the study of all this, according to the author, one can understand the laws of psychology.

Wundt was the first to point out the important role of social processes in the development of mental functions.

Despite Wundt's popularity in the emerging American psychology, his cultural and historical direction practically did not become popular among Americans. They were mainly interested in experimental psychology.

As we have already said, in his research Wundt also used the method of introspection, which modern psychologists consider unscientific. During introspection, a person examines his own feelings. This method is one of the most ancient in science; it was known to ancient thinkers. In particular, this method was widely used by doctors when testing the effect of drugs on themselves. Physicists and physiologists also used introspection (for example, a researcher used some stimulus, and then asked the subject to describe his sensations, so the scientist received information about the functioning of the senses).

The strength of introspection was the fact that only the person experiencing certain experiences can describe them most fully and accurately. This is where the benefits of introspection end, however. Wundt, knowing this, tried to combine introspection with an experimental approach. He conducted introspection experiments in his laboratory in strict accordance with certain rules.

However, even in this form, introspection has not earned scientific recognition. Moreover, even then there was information that these experiments caused serious mental illness in some participants.

Experiments with a metronome became famous. Wundt also conducted them on himself. He listened to the beats of the metronome and checked his sensations. A certain rhythm caused him pleasure at some moments, and discomfort at others. While waiting for the next blow, he experienced some tension, and after the blow, relaxation. When the tempo of the blows increased, he became slightly excited, and when he slowed down, he calmed down. These observations allowed Wundt to construct a three-dimensional model of feelings. It allows any feeling to be measured according to three parameters, and for each of them it is always within a certain range.

The three-dimensional concept of feelings gained some popularity in Germany, but was later refuted. Nevertheless, the very fact of penetrating into the depths of the origin of feelings and sensations was very significant.

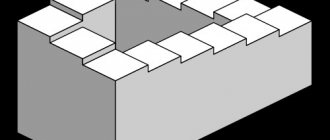

Having learned to decompose consciousness into elements, Wundt noticed that the mind still perceives surrounding objects as a single whole, and not as a set of sensations; So, a tree for us is just a tree, and not just a combination of a special shape, color and lighting. How does this happen? Wundt suggested that consciousness, at the moment of observation, carries out the so-called creative synthesis, due to which a new quality arises from a combination of elements. The brain not only registers incoming data, but also actively “works” with it. This is reminiscent of a chemical reaction in which several starting substances produce a new compound that has properties that the original substances did not have.

The discovery that the whole in our consciousness cannot be reduced to the sum of its parts was subsequently confirmed. In particular, this thesis was officially recognized by representatives of Gestalt psychology in 1912.

Ebbinghaus: laws of memory

Young psychology borrowed its methods from physiology. It did not have its own until the German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus (1850-1909) began the experimental study of associations. In the book “On Memory” (1885), he outlined the results of experiments conducted on himself in order to derive mathematically precise laws by which learned material is stored and reproduced.

Taking up this problem, he invented a special object - meaningless syllables (each syllable consisted of two consonants and a vowel between them, for example, “moya”, “pat”, etc.). To study associations, Ebbinghaus first selected stimuli that did not evoke any associations. He experimented with a list of 2,300 nonsense syllables for two years.

Various options were tried and carefully calculated regarding the number of syllables, the time of memorization, the number of repetitions, the interval between them, the dynamics of forgetting (the “forgetting curve” acquired a classic reputation, which said that approximately half of what was forgotten fell in the first half hour after memorization) and other variables.

In various variants, data were obtained regarding the number of repetitions required for subsequent reproduction of material of varying lengths, forgetting of various fragments of this material (the beginning of a list of syllables and its end), the effect of overlearning (repetition of a list more times than required for its successful reproduction) and etc.

The laws of association thus appeared in a new light. Ebbinghaus did not turn to physiologists for an explanation. But he was not interested in the role of consciousness either. After all, any element of consciousness - be it a mental image or an act - is initially meaningful, and the semantic content was seen as an obstacle to the study of the mechanisms of pure memory.

Ebbinghaus opened a new chapter in psychology not only because he was the first to venture into the experimental study of mnemonic processes, more complex than sensory ones. His unique contribution was determined by the fact that for the first time in the history of science, through experiments and quantitative analysis of their results, psychological laws were discovered that act independently of consciousness, in other words, objectively. The equality of the psyche and consciousness (accepted as an axiom in that era) was crossed out.