The concept of Freudian psychoanalysis

| It has been suggested that Mortido and |

For the album Sole & DJ Pain 1, see Death Drive (album).

| This article lack of information about modern scientific perspective . |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Psychoanalysis |

Concepts

|

Important numbers

|

Important works

|

Schools of thought

|

Training

|

see also

|

|

|

In classic Freudian psychoanalytic theory, the death drive

(German: Todestrieb) is to drive a car towards death and destruction, often expressed in behaviors such as aggression, compulsion to repeat, and self-destruction.[1][2]

This was originally proposed by Sabina Spielrein in her article "Destruction as the Cause of Coming into Being"[3][4] ( Die Destruktion as Ursache des Werdens

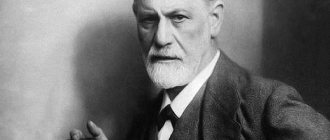

)[5] in 1912. Sigmund Freud in 1920 in

Beyond the Pleasure Principle.

This concept has been translated as “the confrontation between ego and death.

instincts and sexual or life instincts."[6] In The Pleasure Principle

, Freud used the plural "death drive" (

Todestriebe

) much more often than the singular.[7]

The death drive is opposed to Eros, the tendency towards survival, reproduction, sex and other creative, life-producing impulses. The death drive is sometimes called "Thanatos" in post-Freudian thought, complementing "Eros", although this term was not used in Freud's own work, rather introduced by Wilhelm Stekel in 1909 and then by Paul Federn in the present context.[8][9] Subsequent psychoanalysts such as Jacques Lacan and Melanie Klein defended the concept.

Terminology

The standard edition of Freud's works in English confuses two terms that are distinct in German: Instinkt

("instinct") and

Trieb

("drive"), which is often translated as

instinct

;

for example, “the hypothesis of the death instinct

, the task of which is to return organic life to an inanimate state.”[10]

"This equation of Instinkt

and

Trieb

has caused serious misunderstandings."[11][12]

In fact, Freud refers to the term "Instinkt", clearly used elsewhere,[13] and therefore, although the concept of "instinct" can be loosely called "drive", any essentialist or naturalistic connotations of the term should be set aside. In a sense, the death drive is a force that is not essential to the life of an organism (unlike "instinct") and tends to denature it or cause it to behave in ways that are sometimes counterintuitive. In other words, the term “death instinct” is simply a misconception about the death instinct. This term is almost universally known in Freudian scholarship as the "death drive", and Lacanian psychoanalysts often shorten it to simply "the drive" (although Freud postulated the existence of other drives, and Lacan explicitly states in Seminar XI that all drives are partial for the death drive).[14] Modern Penguin Freud translations translate Trieb

and

Instinkt

as "drive" and "instinct" respectively.

Suicide as a political protest

A cold and considered decision to accept death can be an act of good will or even a form of protest.

On June 10, 1963, American newspaper branches in South Vietnam received a message that the next day something important would happen in one of the squares of Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City). Many journalists ignored this news, but some still showed up on June 11 at the appointed time and place. Three Buddhist monks appeared at one of Saigon's busy intersections. One placed a meditation cushion on the road, the other sat on it in the lotus position. The third monk took a can of gasoline from the trunk and doused the man sitting. Having finished reading the mantra, he took out matches and set himself on fire. Monks, passers-by, and even police officers performed prostrations (a type of full bow in Buddhism). One of the monks shouted several times through a megaphone in Vietnamese and English: “A Buddhist monk has committed self-immolation! A Buddhist monk became a martyr!”

The martyr's name was Thich Quang Duc. By self-immolation, he protested against the actions of the South Vietnamese authorities who persecuted Buddhists.

Thich Quang Duc's last words are known from the letter he left: “Before I close my eyes and look towards the Buddha, I respectfully ask President Ngo Dinh Diem to show compassion to the people and ensure religious equality so that the strength of our motherland will be eternal. I call upon Venerables, Reverends, Sangha members and lay Buddhists to show organized solidarity in self-sacrifice for the defense of Buddhism.”

During this period, 70-90% of the country's inhabitants professed Buddhism, but President Ngo Dinh Diem himself was a Catholic. He provided his co-religionists with advantages in careers, business and land distribution, while Buddhists were discriminated against in every possible way.

Catholic priests formed armed groups, forcibly baptized people, and destroyed and looted pagodas.

In early May 1963, authorities banned the Buddhist flag from entering Hue. Believers ignored the ban: on the day of the holiday, a crowd of protesters headed to the government radio station along with the flag. The authorities opened fire and several people were killed. But Ngo Dinh Diem blamed the violence on the Viet Cong, the communist army of North Vietnam. In protest against the government's actions, Thich Quang Duc publicly committed suicide.

Journalist David Halberstam of The New York Times, who witnessed the self-immolation in Saigon, wrote: “I could not cry because of the shock, I could not write or ask questions because of the confusion, I could not even think because I was stunned... He did not move a single muscle, did not make a sound while he was burning; his obvious self-control stood out against the sobbing people around him.”

For their reporting on the self-immolation, Halberstam and photographer Malcolm Brown received a Pulitzer Prize (and Brown also received a World Press Photo prize).

Origin of the theory: Beyond the pleasure principle

Main article: Beyond the pleasure principle

Freud's basic premise was that "the course of mental events is automatically regulated by the pleasure principle... [associated] with the avoidance of unpleasure or the production of pleasure."[15] Three main types of contradictory evidence, difficult to explain in such terms, led Freud, late in his career, to search for another principle in mental life. outside

into the pleasure principle—a quest that will ultimately lead him to the concept of the death drive.

The first problem Freud encountered was the phenomenon of repetition of (war) trauma. When Freud worked with people with trauma (especially trauma suffered by soldiers returning from the First World War), he noticed that subjects often tended to repeat or reenact these traumatic experiences: "dreams occurring in traumatic ones have the characteristic of repeatedly returning the patient to the situation his accident,”[16] contrary to the expectations of the pleasure principle.

Freud discovered a second problem area in children's play (such as Fort/Da

[Next / here] a game played by Freud's grandson, who stages and re-stages the disappearance of his mother and even himself). “How then is his repetition of this painful experience as a game consistent with the pleasure principle?”[17][18]

The third problem arose from clinical practice. Freud discovered that his patients, dealing with repressed painful experiences, were regularly “compelled to repeat

repressed material as contemporary experience instead of...

remembering

it as something belonging to the past."[19] Combined with what he called "the compulsion of fate... found [in] people whose all human relationships have the same result," [20] such evidence led Freud "to substantiate the hypothesis of a compulsion to repeat—something that would seem more primitive, more elementary, more instinctive than the pleasure principle which he rejects.”[21]

He then set out to find an explanation for such compulsion, an explanation that some scientists called "metaphysical biology".[22] In Freud's own words, "What follows is a guess, often a far-fetched guess, which the reader will consider or reject according to his individual preferences."[23] In his search for a new instinct paradigm, he found such problematic repetition in “ the desire in organic life to restore the previous state of affairs

“[24] is the inorganic state from which life arose. From the conservative, restorative character of instinctual life, Freud took his death drive with its “pressure towards death” and the resulting “separation of the death instincts from the life instincts.”[25] saw in Eros. The death drive then manifested itself in the individual being as a force “the function of which is to ensure that the organism follows its own path to death.”[26]

Seeking further potential clinical confirmation of the existence of such a self-destructive force, Freud found this by revising his views on masochism - which had previously been "seen as sadism directed against the subject's own ego" - to allow for it. "there could

to be such a thing as primary masochism is a possibility that I disputed “[27] before. However, even with this support, he remained very uncertain until the end of the book about the provisional nature of his theoretical construct: what he called “our whole artificial structure of hypotheses.”[28]

Although Spielrein's article was published in 1912, Freud initially resisted the concept, considering it too Jungian. However, Freud eventually accepted the concept, and in subsequent years extensively developed the preliminary foundations he laid down in Beyond the Pleasure Principle

.

In The Ego and the Identity

(1923) he developed his argument to state that "the death instinct might thus express itself—though probably only in part—as an

instinct of destruction

directed against the external world."[29] The following year he would explain more clearly that “the libido is designed to make the instinct of destruction harmless, and it accomplishes this task by largely diverting this instinct outward... The instinct is then called the destructive instinct. instinct of mastery or will to power,”[30] is perhaps a much more recognizable set of manifestations.

At the end of the decade in Civilization and its discontents

(1930), Freud admitted that “At first I only tentatively put forward the views that I have here developed, but in time they have taken such possession of me that I can no longer think otherwise. ".[31]

Why did the magicians want to free themselves from the flesh?

The culture and mythology of death are rooted in early systems of opposition between two fundamental, equal world forces: God and the devil in religious consciousness, mental and physical in philosophical consciousness, black and white in everyday life. This dualism in the perception of life and death in many cultures is expressed through the concept of time.

Earthly birth is preceded by death; dying, the body is reunited with the earth, and the soul with the higher spirit. Death also means rebirth, and this idea is reflected in the ancient symbol of the dragon (snake) biting its own tail.

It is found in a number of cultures, but has become known by the name the Greeks gave it, ouroboros. The meaning of this symbol is formulated as “the beginning is where the end is.” It is used in alchemy, Gnosticism and even psychoanalysis to denote the self-generating process of self-destruction and fertility.

Another aspect of death is the unknown, the incomprehensibility, because no one has ever returned from “there” with concrete evidence. From here the mythological consciousness takes the idea of omniscience of the dead - after all, the deceased joins the secret knowledge of the gods and thus himself becomes an object of worship. The cult of ancestors was widespread in the ancient world, in the Ancient East, in Central America, as well as among the ancient Slavs. The deified ancestor protects his family; priests and sorcerers turned to him for predictions of the future or in search of sacred knowledge.

From this form of shamanism originate the rituals of necromancy - practical magic that was used to establish contact with the dead or tell fortunes on corpses.

According to Pliny the Elder's Natural History, magical rites were created by Zarathustra in Persia, magic also existed in Babylon and then spread to the Greco-Roman world.

Strabo, in his work Geography, speaks of “death spellcasters” as the main predictors among Persian magicians.

Egyptian magical papyri describe the ritual of summoning the spirit of a deceased person. Egyptologist Robert Richter believes that such practices were not borrowed from other traditions, but developed from indigenous beliefs and rituals.

To learn more about magic, the philosophers Pythagoras, Empedocles, Democritus and Plato went on long journeys, and when they returned, they talked about what they saw, and, as Pliny believed, they most contributed to the spread of the magical teachings of the work of Democritus. The oldest artistic description of the ritual of necromancy can be found in Homer's Odyssey.

Following the instructions of the sorceress Circe, Odysseus goes to the underworld to find out how he can return home to Ithaca. Homer describes the ritual itself in detail. Arriving at the entrance to the kingdom of the dead, Odysseus and his companions dig a hole and sacrifice animals over it, their blood calling on the spirits of the dead. The travelers then make an offering to the underground gods Hades and his wife Persephone. Odysseus' goal is to summon the shadow of the soothsayer Tiresias. He appears and, having drunk black blood, gives Odysseus an answer.

In the Middle Ages, the pursuit of magic and science was not very different. Many people believed that one could know the future by observing the stars, and astrologers prospered in royal courts as important advisors on many matters. Astrology was even taught in universities and was considered the highest level of mathematics and an integral part of medicine. Almichy and necromancy were the subject of no less interest to learned men of the Middle Ages. They believed in a certain supernatural power of the words of sacred texts, considered them secret writing and interpreted the Bible allegorically. They saw a mystical meaning in every number in the Holy Scriptures and believed that every letter contained knowledge with the help of which they could control all processes in the Universe.

The Italian thinker Pico della Mirandola insisted that magical and cabalistic (derived from Jewish mysticism) teachings proved the divinity of Christ better than any other sciences.

The German humanist Johann Reuchlin associated the letters in Holy Scripture with individual angels. Inspired by Reuchlin's works De verbo mirifico and De arte cabbalistica, Agrippa of Nettesheim proclaimed that he who knows the true pronunciation of the name of Yahweh has “peace in his mouth.” Agrippa's occult works were highly praised by the 19th century kabbalist Eliphas Levi, who described communication with the spirit of the Greek philosopher Apollonius of Tyana as a ritual with magical signs and objects, the result of which is a somnambulistic trance.

Personal astrologer and advisor to Queen Elizabeth I, John Dee, who had a reputation as a magician, once declared that he had a magic mirror that could show fate. But he was unable to discern anything in him until the necromancer Edward Kelly offered himself as a medium. Kelly later stated that angels spoke to him through a magic mirror in the language of Enoch (however, he was later accused of quackery).

According to all these mystics, if the ethereal entity frees itself from the framework of the mortal mind, it will be able to comprehend what lies beyond human perception.

The idea that the flesh is only an obstacle in achieving sacred knowledge is also present in the ascetic practices of various religious and philosophical teachings.

Initially, in Ancient Greece, asceticism was called the exercise of virtue. It consisted of self-restraint and abstinence from satisfying certain human needs - food, clothing, sleep, sex life, as well as refusal of entertainment and intoxicating drinks.

It was believed that thanks to such practices a person overcomes himself, grows in the knowledge of the Supreme and achieves a full spiritual life.

A representative of the school of religious existentialism, Nikolai Berdyaev, understands asceticism as a metaphysical and religious principle and formulates two main forms of ascetic metaphysics. The first is the recognition of the world and life as evil, as in Hinduism, which considers the world illusory and evil; the ultimate expression of such a philosophy is Buddhism. Another form of ascetic metaphysics is found in Greece - this is, for example, Neoplatonism, which preaches deliverance from the material world. Greek philosophical thought always saw the source of evil in matter, although it understood it differently than Descartes and the thinkers of the 19th and 20th centuries. From this point of view, the lower (matter) cannot be raised to the higher (spirit).

Asceticism here means cutting off the spirit from the material principle: “evil” matter cannot be defeated or transformed, one can only separate from it.

In addition to spiritual asceticism, Berdyaev also considers sports and revolutionary asceticism. In his opinion, serious training is required from the athlete - not only physical, but also mental, because he risks his life and must be psychologically prepared for death. Discussing revolutionary asceticism, Berdyaev turns to Nechaev’s “Catechism of Revolution” and writes that a revolutionary is a doomed person who has no personal interests, because everything in him is captured by one passion.

Philosophy

See also: Philosophy of “will” in Schopenhauer

From a philosophical point of view, the death drive can be considered in connection with the works of the German philosopher. Arthur Schopenhauer. His philosophy, set forth in The World as Will and Representation

(1818) postulates that everything exists according to a metaphysical “will” (more clearly,

will live

[32]), and this pleasure confirms this will. Schopenhauer's pessimism led him to believe that the assertion of "will" was a negative and immoral matter due to his belief that life brought more suffering than happiness. The death drive would seem to manifest itself as a natural and psychological negation of “will.”

Freud was well aware of such possible connections. In a 1919 letter, he wrote that regarding "the subject of death [that I] have come across a strange idea through the drives and now have to read all sorts of things relating to it, for example, Schopenhauer."[33]Ernest Jones (who, like many analysts, , was not convinced of the need for a death drive other than the instinct of aggression), believes that "Freud seems to have fallen into the position of Schopenhauer, who taught that 'death is the goal of life'." .[34]

However, as Freud told the imaginary auditors of his New Introductory Lectures

(1932): "Perhaps you will shrug your shoulders and say: 'This is not natural science, this is the philosophy of Schopenhauer!' “But, ladies and gentlemen, why shouldn’t a bold thinker guess something that is subsequently confirmed by sober and painstaking detailed research? “[35] He then added that “what we are saying is not even the real Schopenhauer... we are not losing sight of the fact that there is life and also death. We recognize two basic instincts and give each of them its own purpose." .[36]

Ants and hair shirts: why did Christians torture themselves?

In early Christianity, ascetics were those who spent their lives in solitude and self-torture, in fasting and prayer.

Traditional self-torture is common in various cultures. The Satere Mawe Indians of Brazil have a male initiation rite during which the young man must endure painful ant bites. The festival in honor of the Hindu god Murugan, leader of the army of gods, includes wearing shoes with nails.

The Islamic holiday of Ashura is widely known, it is celebrated by all Muslims, but its meaning varies in different branches of the religion. Sunnis consider the tenth day of Muharram a significant date: it was on this day that the Almighty created Adam, the Great Flood ended and the prophet Musa (Moses) escaped from Egypt. But for Shiites, this is a day of mourning for religious martyrs, primarily for Hussein ibn Ali. Mourning lasts the first ten days of the month of Muharram, and the culmination of mourning ceremonies occurs on the day of Ashura. On October 10, 680, Imam Hussein, his brother Abbas and 70 of their companions were killed in the Battle of Karbala. In memory of their martyrdom, Shiites organize religious mysteries - tazias, which include self-flagellation, symbolizing Hussein's suffering before death. During the ritual, believers beat themselves in the chest with their fists and hit themselves on the back with a zanjeer - a chain with blades attached to it. Each blow rips open the skin and leaves bloody wounds. Some men cut the skin on their heads and blood floods their faces.

Among Christians, religious self-torture appeared under the influence of the traditions of the ancient Jews, who wore rough clothes made of goat hair as a sign of sadness and memory of the dead.

All close relatives of the deceased had to wear sackcloth or hair shirt; in special cases, these clothes made of coarse hair were not removed even at night.

In the Middle Ages, a hair shirt was a mandatory attribute of monasticism. Monks and communicants wore these clothes as a sign of humility and frailty of the flesh. Suffering from constant itching and skin irritation had to be overcome with fortitude and prayer. Wearing a hair shirt was an integral part of serving God, and wounds on the body were perceived as evidence of suffering for Christ and his faith.

Devotion to faith, expressed in self-sacrifice, is the only justification for voluntary death (that is, suicide) in Abrahamic religions and Eastern religious and philosophical teachings. In Christianity, Judaism and Islam, suicide is condemned because, in addition to murder, it involves the sin of despondency. In addition, in Christianity, suicides are deprived of funeral services, and sin can be forgiven only if the person is declared insane.

Cultural Supplement: Civilization and Its Discontents

Main article: Civilization and its discontents

Freud applied his new theoretical construct to Civilization and Its Discontents

(1930) to the difficulties inherent in Western civilization - in fact, in civilization and in social life in general. In particular, given that "a part of the [death] instinct is directed into the outer world and comes out as the instinct of aggressiveness," he saw "the tendency to aggression ... [as] the greatest obstacle to civilization." [37] The need to overcome such aggression entailed the formation of a [cultural] superego: “We are even guilty of heresy in attributing the origin of conscience to this inward distraction of aggressiveness.”[38] The presence thereafter in the individual of the superego and the associated sense of guilt - "Civilization thus gains power over the individual's dangerous desire for aggression, ... creating in him an agency that will watch over him"[39] - leaves a constant feeling of anxiety inherent civilized life, thereby providing a structural explanation for the "sufferings of civilized man".[40]

Freud made another connection between the life group and innate aggression, where the former interacts more closely to direct aggression towards other groups, an idea later taken up by group analysts such as Wilfred Bion.

Why would God sacrifice himself?

The central idea of cosmogony in many cultures is that of the “primordial sacrifice.” Any act of creation implies some kind of sacrifice in the cycle of birth and rebirth and identifies man with the cosmos. Sacrifice is also an act of submission to divine providence through offering oneself to God's will, atonement. According to the myths of different cultures, the world was created from parts of the object of sacrifice.

Among the ancient Germans, the younger gods kill their ancestor, the ice giant Ymir, and from parts of his body create the Universe: from flesh - land, from blood - water, from bones - mountains, from teeth - rocks, from hair - a forest, from a brain - clouds, and from the skull - the vault of heaven.

In Sumerian-Babylonian mythology, the goddess of salty waters and the personification of primary chaos, Tiamat, dies in a battle with the god Marduk, when he dismembers her into two parts with an arrow. From her body he creates the world and becomes the supreme deity. From the lower part he made the earth, from the upper part - the sky, from the eyes - the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, and Tiamat's tail became the Milky Way.

When a person sacrifices himself, the spiritual energy gained is proportional to the significance of what was lost. All forms of suffering can be sacrificed if they are recognized and accepted wholeheartedly. The physical and negative signs of sacrifice (mutilation, flagellation, self-abasement and cruel punishment or misfortune) are symbols and an integral part of the aspirations of the spiritual order.

The self-sacrifice of a deity is an archetypal motif in world culture. Argentine playwright Jorge Luis Borges, in his typology of plots, calls the suicide of God one of the four stories that humanity constantly retells. The other three are stories about the siege of a city doomed to fall (Troy), the return home (The Voyage of Odysseus), and the search for treasure (The Holy Grail, The Golden Fleece).

Borges calls the suicide of a deity (in addition to the crucifixion of Christ) the myth of the sacrifice of the supreme god of the Scandinavians Odin, the most mysterious figure in the pantheon. He has one eye: Odin gave his eye to the giant Mimir in exchange for the opportunity to drink from a source that gives wisdom. The sacrifice that Borges speaks of is set out in the “Speech of the High One” in the collection “Elder Edda”. In it, the Tall One (aka Odin) tells how, having pierced his body with a spear, he sacrifices himself to himself. Any sacred sacrifice takes place in the center of the world, so for nine days and nights Odin hangs on the branches of the world tree Yggdrasil. After this period, the god falls to the ground and receives magic runes:

I know, I hung in the branches in the wind for nine long nights, pierced by a spear, dedicated to Odin, as a sacrifice to myself, on that tree whose roots are hidden in the depths of the unknown. No one fed me, no one gave me water, I looked at the ground, I picked up the runes, groaned and picked them up - and fell from the tree.

The continuing development of Freud's views

It has been suggested that in the last decade of Freud's life his view of the death drive changed somewhat, and "emphasis was placed on the manifestations of the death drive. outward

".[41] Given the "universal prevalence of non-erotic aggressiveness and destructiveness," he wrote in 1930: "I therefore adhere to the view that the tendency to aggression is the original self-existent instinctive predisposition of man."[42]

In 1933, he acknowledged his original formulation of the death drive as "the improbability of our assumptions." Indeed, a strange instinct aimed at destroying one’s own organic home! "[43] Moreover, he wrote that "our hypothesis is that there are two essentially different classes of instincts: the sexual instincts, understood in the broadest sense - Eros, if you prefer that name - and the aggressive instincts, the aim of which is destruction." [44] In 1937 he went so far as to privately suggest that "we should have a clear schematic picture if we suppose that originally, at the beginning of life, all libido was directed inward and all aggressiveness outward."[45 ] In his last works it was a contrast between “two basic instincts, Eros

and

the destructive instinct

... our two primitive instincts,

Eros

and

destructiveness

,[46] on which he laid emphasis. However, his belief in the "death instinct... [as] a return to an earlier state... to an inorganic state"[47] continued to the end.

Possible direction of mortido

Mortido is energy that is directed to creation through sublimation, if we are talking about a highly developed personality. If the individual is not sufficiently developed, then this force is directed against him. He begins to destroy himself psychologically, and then psychosomatics may arise. Mortido is a destructive force. It has a meaning opposite to libido. If we are talking about directing energy outward, this is anger, irritation, aggression, the desire to destroy everything around. If a person redirects this energy into a transformational direction, then this is a strong desire to achieve a high goal, sublimation into great things.

Analytical technique

As Freud wryly noted in 1930, “the supposition of the existence of a death or destruction instinct has met with resistance even in analytic circles.”[48] Indeed, Ernest Jones would comment Beyond the Pleasure Principle

that the book not only "showed a boldness of conjecture that was unique to all his writings" but was "even more remarkable for being the only book by Freud that did not receive much recognition from his followers."[49]

Otto Fenichel, in his brief overview of the first half-century of Freudianism, concluded that "the facts on which Freud based his concept of the death instinct in no way require the assumption ... of a true instinct for self-destruction."[50] Heinz Hartmann set the tone for ego psychology when he "preferred...to dispense with Freud's other, largely biologically oriented set of hypotheses about the 'life instincts' and the 'death instincts'."[51] in object relations theory, among independent groups, "the most common denial was the disgusting concept of the death instinct."[52] Indeed, "for most analysts, Freud's idea of the primitive death drive, of primary masochism... was marred by problems."[53]

However, the concept has been defended, expanded and promoted by some analysts, mainly those closely associated with the psychoanalytic mainstream; while among the more orthodox, perhaps "those who, unlike most other analysts, take Freud's doctrine of the death drive seriously, C. R. Eissler was the most convincing - or the least unconvincing."[54]

Melanie Klein and her closest followers believed that "from birth the infant is subject to anxiety caused by an innate polarity of instincts - an immediate conflict between the life instinct and the death instinct";[2] and the Kleinians indeed built much of their theory of early childhood on the outward deviation of the latter. “This deviation of the death instinct, described by Freud, from the point of view of Melanie Klein, consists partly of projection, partly of the transformation of the death instinct into aggression.”[2]

The French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacanceau, for his part, condemned “the refusal to accept this culminating point of Freud’s teaching ... by those who carry out their analysis on the basis of the concept of the ego

... the death instinct, the riddle of which Freud offered us at the peak of his experience."[55]

Characteristically, he emphasized the linguistic aspects of the death drive: “the symbol replaces death in order to master the first swelling of life...There is therefore no longer any need to resort to the outdated concept of primordial masochism. to understand the reason for repeated games in... his Fort!

and in his

Yes!

.”[56]

Eric Berne, too, would proudly proclaim that he, "besides repeating and confirming Freud's generally accepted observations, also believes the same as he does regarding the death instinct and the pervasive compulsion to repeat."[57]

For the twenty-first century, "the death drive today... remains a highly controversial theory among many psychoanalysts... [almost] as many opinions as there are psychoanalysts."[58]

Freud's conceptual contrast between death and the eros drive in the human psyche was applied in Walter A. Davis's work. Disappearance: Historicity, Hiroshima and the Tragic Imperative

[59] and

Reign of Death: American Psyche since 9/11.

[60] Davis described the social reaction to both Hiroshima and 9/11 from the Freudian perspective of the power of death. Unless they consciously take responsibility for the damage from these reactions, Davis argues that Americans will repeat them.

Code of Honor: Suicide as a Duty

If in European Christian culture there is a strict ban on suicide, then, for example, in Shintoism in Japan this has never happened. According to Christians, the human body belongs to God who created it, and by taking his own life, a person goes against his will and commits a sin. In Japan, it was believed that a person’s body belongs to his parents or master and he must serve them with his body. Harakiri, or seppuku, is a method of ritual suicide adopted among samurai in the Middle Ages and practiced until the 20th century.

The samurai's body belongs to his daimyo (prince), so seppuku is an element of power relations, the relationship between sovereign and vassal.

Therefore, ritual suicide was practiced if the master himself sentenced his subordinate to such execution. If the samurai was slandered, accused of treason, he could resort to hara-kiri in order to thus prove his innocence and loyalty to the daimyo.

This method of suicide is a procedure of cutting open the abdomen, which is extremely painful and excruciating. The Japanese believed that the stomach is the most important part of the body, which contains the vital center of the body. During harakiri, a person eliminated this vital force.

Seppuku was performed in front of many witnesses, and over the suicide stood the kaishaku - a warrior who, after performing the death ritual, had to cut off the samurai's head so that no one could see the face of the deceased, distorted with pain.

In Japanese society, such an execution was considered honorable; it was the privilege exclusively of samurai. Firstly, a person took his own life, and did not accept death at the hands of another. Secondly, such torment is a test that a samurai passes with dignity, dying with honor. If a person was sentenced to seppuk, his family was not persecuted and retained their surname and property.

Suicide was an expression of devotion not only in Japan. Self-immolation of a widow after the death of her husband is common in many ancient Indo-European societies. In Ancient Rus' there was a tradition of burning his slave with the body of the owner. One of Odin’s instructions in the “Speeches of the High One” reads: “Praise your wives at the stake.” In Hinduism, there is a legend about the goddess Sati, who became the wife of the god Shiva against the wishes of her father. Sati's father Daksha gathered the gods for a yajna - a sacrifice, but did not invite Shiva, thus demonstrating his attitude towards his daughter's marriage. The insulted Sati, unable to bear the humiliation, threw herself into the sacred fire and burned.

The widow's self-immolation ritual takes its name from this Indian goddess; it symbolizes a woman's unconditional devotion to her husband and proves her virtue.

In India, the ritual of burning widows is not practiced everywhere. Indian society is still divided into castes, and not all of them encourage such brutal disposal of widows, so the social background of the woman matters here. The practice of sati has largely taken root in areas where remarriage is prohibited, in the upper castes and among those seeking social status, such as in Rajasthan and some districts of Uttar Pradesh. It is believed that a woman should make such a choice voluntarily, but it is possible that the community put pressure on the widow.

Since in India they are ready to marry off a girl at the age of 6, and the age difference with her husband could be huge, it often happened that the husband died earlier. Indian tradition requires the widow to cut her hair, take off her elegant clothes and dress in white. From now on, she is not allowed to participate in the celebrations and will only eat a strictly limited amount of food per day. The family could refuse her, and often widows were forced to sleep on the bare ground and beg.

There was only one alternative to such a life, and from the point of view of an Indian woman, it seems promising, because a righteous wife, upon rebirth, may be lucky enough to step through several steps of incarnation at once.

Hindu believers believe that the will that leads a widow to the fire is the act of the goddess Sati, and the goddess is embodied in the woman herself at that moment.

Back in 1829, the British colonial authorities passed a law making suicide a crime. After this, the self-immolation of widows seemed to stop, but nevertheless, similar things could happen in the 20th century.

One of the most famous self-immolations in the modern world was the case in 1987 of 18-year-old Roop Kanwar, whose husband died of appendicitis just 8 months after their wedding. The next day, Roop, dressed in her wedding attire, threw herself into the funeral pyre of her husband. The arriving police arrested and interviewed about a hundred witnesses, suspecting that the girl was put under pressure by her husband's relatives. Articles appeared in the press condemning this anachronism and its supporters, who cited ancient texts in its defense. The Indian government responded quickly and harshly: a new law threatened life imprisonment or death for incitement to commit sati.

Recommendations

- Eric Berne, What do you say after you say hello?

(London, 1975) pp. 399-400. - ^ a b c

Hannah Segal,

Introducing the Work of Melanie Klein

(London, 1964), p. 12. - Spielrein, Sabine (April 1994). "Destruction as a cause of origin." Journal of Analytical Psychology

.

39

(2): 155–186. Doi:10.1111/j.1465-5922.1994.00155.x.Free pdf full essay Archived 2016-03-06 in the Wayback Machine by the Arizona Psychoanalytic Society. - Spielrein, Sabine (1995). "Destruction as the cause of formation." Psychoanalysis and Modern Thought

.

18

(1):85–118. - Spielrein, Sabine (1912). " Die Destruktion as Ursache des Werdens

."

Jahrbuch für Psychoanalytische und Psychopathologische Forschungen

(in German).

IV

: 465–503. - Sigmund Freud, “Beyond the Pleasure Principle” in On Metapsychology

(Middlesex, 1987), p. 316. - See occurrences of "death chase" and "death drive".

- Jones, Ernest (1957) [1953]. The life and work of Sigmund Freud.

Volume 3 .

New York: Basic Books. p. 273. It is a little strange that Freud himself never, except in conversation, ever used the term for the death instinct Thanatos

, which has since become so popular. At first he used the terms “death instinct” and “destructive instinct” indiscriminately, alternating between them, but in his conversation with Einstein about war he made the distinction that the first is directed against the individual, and the second, a derivative of it, is directed outward. Stekel in 1909 used the word Thanatos to refer to the death wish, but it was Federn who introduced it into its current context. - Laplanche, Jean; Pontalis, Jean-Bertrand (2018) [1973]. "Thanatos". The Language of Psychoanalysis

. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-92124-7. - Sigmund Freud, “The Ego and the Id,” in On Metapsychology

(Middlesex, 1987), p. 380. - Otto Fenichel, The Psychoanalytic Theory of Neuroses

, (London, 1946), p. 12. - Laplanche, Jean; Pontalis, Jean-Bertrand (2018) [1973]. "Instinct (or drive)."

- Nagera, Umberto, ed. (2014) [1970]. "Instinct and Drive (pp. 19ff)." Basic psychoanalytic concepts of instinct theory

. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-67045-2. - Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis

. WW Norton. ISBN 9780393317756. - Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, p. 275.

- Freud, Beyond, p. 282.

- Freud, Beyond, p. 285.

- Clark, Robert (24 October 2005). "Compulsion to repeat." Literary Encyclopedia

. Retrieved March 15, 2022. - Freud, "Beyond" p. 288.

- Freud, "Beyond" p. 294 and page 292.

- Freud, Beyond, p. 294.

- Schuster, Aaron (2016). The problem is with pleasure.

Deleuze and psychoanalysis . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. n.. ISBN 978-0-262-52859-7. - Freud, Beyond, p. 295.

- Freud, Beyond, p. 308.

- Freud, Beyond, pp. 316 and 322.

- Freud, Beyond, p. 311.

- Freud, Beyond, p. 328.

- Freud, Beyond, p. 334.

- Freud, "Ego/Identifier", p. 381.

- Freud, "The Economic Problem of Masochism" in On Metapsychology

, paragraph 418. - Sigmund Freud, “Civilization and Its Discontents,” in Civilization, Society and Religion

(Middlesex, 1987), p. 311. - Schopenhauer, Arthur (2008). The world as will and representation

. Translated by Richard E. Aquila and David Carus. New York: Longman. - Quoted in Peter Guy, Freud: A Life for Our Times

(London, 1989), p. 391. - Ernest Jones, The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud

(London, 1964), p. 508. - Sigmund Freud, New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis

(London, 1991), pp. 140-1. - Freud, New

, p. 141. - Freud, Civilization

pp. 310 and 313. - Freud, "Why War?" in Civilization

, paragraph 358. - Freud, Civilization

, p. 316. - Jacques Lacan, Ecrits: A Selection

(London, 1997), p. 69. - Albert Dixon, "Editor's Introduction", Civilization

, p. 249. - Freud, Civilization

, pp. 311 and 313. - Freud, New

, p. 139. - Freud, New

, p. 136. - Freud, quoted by Dixon, Civilization

, p. 249. - Sigmund Freud, Standard Version

vol. xxiii (London, 1964), pp. 148 and 246. - Freud, SE

, xxiii, pp. 148-9. - Freud, Civilization

, p. 310. - Jones, Life

, p. 505. - Otto Fenichel, The Psychoanalytic Theory of Neuroses

(London, 1946), p. 60. - Quoted in Gay, Freud

, pp. 402-3n. - Richard Appignanesi, ed., Introducing Melanie Klein

(Cambridge, 2006), p. 157. - Gay, Freud

, paragraph 402. - Gay, page 768.

- Lacan, Ecrits

, para. 101. - Lacan, Ecrits

pp. 124 and 103. - Eric Berne, What do you say after you say hello?

(London, 1975) pp. 399-400. - Jean-Michel Quinodos, Reading Freud

(London, 2005), p. 193. - Davis, Walter A. (2001). Deracination;

Historicity, Hiroshima and the Tragic Imperative . Albany: State University of New York. ISBN 978-0-79144834-2. - Davis, Walter A. (2006). Kingdom of Death Dreams

. London: Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-74532468-5.

Excerpt characterizing Mortido

- Ah! voyons. Contez nous cela, vicomte,” said Anna Pavlovna, joyfully feeling how this phrase resonated with something a la Louis XV, “contez nous cela, vicomte.” The Viscount bowed in submission and smiled courteously. Anna Pavlovna made a circle around the Viscount and invited everyone to listen to his story. “Le vicomte a ete personnellement connu de monseigneur,” Anna Pavlovna whispered to one. “Le vicomte est un parfait conteur,” she said to the other. “Comme on voit l'homme de la bonne compagnie,” she said to the third; and the Viscount was presented to society in the most elegant and favorable light, like roast beef on a hot platter, sprinkled with herbs. The Viscount was about to begin his story and smiled subtly. “Come here, chere Helene,” Anna Pavlovna said to the beautiful princess, who was sitting at a distance, forming the center of another circle. Princess Helen smiled; she rose with the same unchanging smile of a completely beautiful woman with whom she entered the living room. Slightly rustling with her white ball gown, decorated with ivy and moss, and shining with the whiteness of her shoulders, the gloss of her hair and diamonds, she walked between the parted men and straight, not looking at anyone, but smiling at everyone and, as if kindly granting everyone the right to admire the beauty of her figure , full shoulders, very open, according to the fashion of that time, chest and back, and as if bringing with her the glitter of the ball, she approached Anna Pavlovna. Helen was so beautiful that not only was there not a shadow of coquetry visible in her, but, on the contrary, she seemed ashamed of her undoubted and too powerfully and victoriously effective beauty. It was as if she wanted and could not diminish the effect of her beauty. Quelle belle personne! - said everyone who saw her. As if struck by something extraordinary, the Viscount shrugged his shoulders and lowered his eyes while she sat down in front of him and illuminated him with the same unchanging smile. “Madame, je crains pour mes moyens devant un pareil auditoire,” he said, tilting his head with a smile. The princess leaned her open full hand on the table and did not find it necessary to say anything. She waited smiling. Throughout the story, she sat upright, occasionally looking at her full, beautiful hand, which had changed its shape from the pressure on the table, or at her even more beautiful chest, on which she was adjusting the diamond necklace; she straightened the folds of her dress several times and, when the story made an impression, looked back at Anna Pavlovna and immediately took on the same expression that was on the face of the maid of honor, and then again calmed down in a radiant smile. Following Helen, the little princess walked from the tea table. “Attendez moi, je vais prendre mon ouvrage,” she said. – Voyons, a quoi pensez vous? - she turned to Prince Hippolyte: - apportez moi mon ridicule. The princess, smiling and talking to everyone, suddenly made a rearrangement and, sitting down, cheerfully recovered.

further reading

- Otto Fenichel, "Critique of the Death Instinct" (1935), in Collected Papers

, 1st series (1953), 363-72. - K. R. Eissler, "Death instinct, ambivalence and narcissism", Psychoanalytic Study of the Child

, XXVI (1971), 25-78. - Rob Wetherill, The Death Attraction: New Life for a Dead Object?

(1999). - Niklas Hedgebeck, The Death Attraction: Why Societies Self-Destruct

Gaudium; Reprint edition. (2020). ISBN 978-1592110346.