At one time, psychoanalysis became a kind of revolution in psychology. The prevailing point of view that all human actions are the result of the activity of his consciousness gave way to a theory where human actions are the result of the struggle of suppressed aspirations and prevailing ideals, and consciousness is only a part of the psyche, and not its essence. This idea forced psychologists to reconsider their views and turn their attention to where all human passions are stored - to the unconscious.

Instead of introducing

Speaking about psychoanalysis, it must be said that it is divided into classical and modern. When we talk about the former, we primarily refer to the theory developed by the Austrian psychologist Sigmund Freud (1856 - 1939). It was he who first used this term to designate a new method of studying and treating mental disorders.

Subsequently, thanks to his students and followers, the theory developed, grew and acquired new ideas. The development of psychoanalysis was facilitated by Alfred Adler and C. G. Jung, and later by neo-Freudians Erich Fromm, Karen Horney, Harry Stack Sullivan, Jacques Lacan and others. Their activities led to the fact that modern psychoanalysis is difficult to imagine as a unified theory. It manifests itself rather as a combination of different directions and practical approaches to solving the problem of the essence of the human psyche.

Basic provisions of the psychoanalytic philosophy of S. Freud

Sigmund Freud is an Austrian psychologist, neuropathologist, psychiatrist; he is characterized by the study of the phenomena of the unconscious, their nature, forms and methods of manifestation.

In the article My Life and Psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud wrote: I was born on May 6, 1856 in Freiberg in Moravia, a small town in what is now Czechoslovakia. My parents were Jews, and I myself remain a Jew. Among twentieth-century psychologists, Dr. Sigmund Freud occupies a special place. His major work, The Interpretation of Dreams, was published in 1899. Since then, various scientific authorities in psychology have risen, replacing each other. But none of them still arouses such enduring interest as Freud and his teaching. This is explained by the fact that his works, which changed the face of psychology in the twentieth century, illuminated the fundamental issues of the structure of the inner world of the individual, his motives and feelings, conflicts between his desires and sense of duty, the causes of mental breakdowns, a person’s illusory ideas about himself and others.

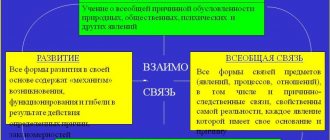

It is known that the main regulator of human behavior is consciousness. Freud discovered that behind the veil of consciousness lies a deep, seething layer of powerful aspirations, impulses, desires that are not recognized by the individual. As an attending physician, he was faced with the fact that these unconscious experiences and motives can seriously burden life and even cause neuropsychiatric diseases. This led him to look for ways to free his patients from conflicts between what their conscious minds were telling them and their hidden, blind, unconscious motives. Thus was born the Freudian method of healing the soul, called psychoanalysis. Freud's theory has become firmly established in textbooks on psychology, psychotherapy, and psychiatry in many countries. He influenced other humanities - sociology, pedagogy, anthropology, ethnography, philosophy, as well as art and literature, and the Freudian methodology of cognition of social phenomena, requiring the disclosure of the underlying unconscious mechanisms, repressed desires, was widely used by Freud's followers and grew into a kind of philosophy. Psychoanalytic philosophy, the empirical basis of which is psychoanalysis, continues and deepens the irrationalistic tendencies of the Philosophy of Life, and from its position seeks to explain personal, cultural and social phenomena.

The revolution in natural science demanded a worldview interpretation of scientific discoveries, and this gave new impetus to Freud's interest in philosophy. In 1874-1875 listened to a series of lectures by the German idealist philosopher F. Brentano (1833-1917). His doctrine of mental actions as directed actions of the soul, his polemics with the English psychiatrist J. Model on the problems of the unconscious aroused Freud's keen interest.

Passion for positivist philosophy was a fairly common phenomenon among natural scientists of that time and was explained by a certain closeness to positivism, that is, that wing of it that goes back to natural-scientific materialism. The influence of positivism on the formation of his views was significantly adjusted by the nature of his scientific interests. He did not believe in metaphysics, opposing it to a worldview based on a system of knowledge about the world. He was convinced of the unity and universality of the laws of nature. However, Freud's materialism was limited in nature, that is, it was spontaneous, unformed. This formlessness, the lack of serious theoretical and cognitive preparation, and poor knowledge of dialectics led to the fact that, being a materialist at the bottom, that is, when explaining natural phenomena, Freud remained an idealist at the top, that is, when solving social and epistemological problems. He emphasized the fundamental discrepancy between materialism and the entire broad movement of positivism. Freud's ideological evolution fully confirmed this. Having abandoned the scalpel and microscope a decade and a half later, Freud essentially parted with materialism, although he never abandoned the beliefs of his youth. The moment has come when he begins independent scientific activity.

Returning to classical psychoanalysis

Sigmund Freud is rightfully considered the founder of this branch of psychology, but it should be mentioned that certain elements of what we now call psychoanalysis appeared earlier, in the works of various philosophers.

For example, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) was the first to clearly formulate the concept of the unconscious, introducing the concept of the “unconscious psyche.” He believed that the universe consists of many monads - immaterial substances capable of perceiving reality. At the same time, a person, or rather his soul, is also a monad with a high level of perception, reaching the level of consciousness. At the same time, he did not identify consciousness with the psyche, since he believed that the soul also has perceptions that it is not aware of (the activity of “small perceptions”).

G. Leibniz's ideas about the unconscious were further developed in the works of G. Helmholtz, C. Darwin, and the German psychologist W. Wundt made a great contribution to the systematization of the idea of the unconscious.

Sigmund Freud also significantly changed and expanded ideas about the unconscious. In his works, he explains the process of formation of the unconscious as a result of the displacement from consciousness of elements that are unwanted for some reason.

In addition to dividing the psyche into areas of the conscious and unconscious, he also introduced the concept of three mental authorities - structures of the psyche that predominate in one area or another. He called these structures “I”, “It” and “Super-ego”.

These and some other ideas formed the basis of the theory of psychoanalysis, so they will be discussed further.

History of creation

The psychoanalytic method was developed by Freud based on the experiments of the Viennese doctor Joseph Breuer. This doctor was treating a patient suffering from a severe form of hysteria. In order to understand the causes of deep mental turmoil, Breuer decided to use hypnosis. It was this method that forced the patient to talk about the circumstances that preceded the illness. As it became clear, most of the symptoms of hysteria were the result of affective experiences that the girl experienced while on duty at the bedside of her beloved, seriously ill father. The doctor made his patient not only remember this period. During his sessions, the girl once again experienced her affective states. As a result, all symptoms of the disease disappeared. Breuer called the treatment method he created catharsis, which translated from Greek means “purification.”

Based on such experiments, Freud suggested that the mental area is not at all reducible to the conscious. Often the true motives of a person’s behavior are far beyond his consciousness. Subsequently, Freud began to use the cathartic method himself. He did this not even in the patient’s hypnotic state, but in a normal one. The results of such studies have convincingly proven that the human psyche has a diverse and complex structure.

Before Freud, doctors could not explain some clinical signs of hysteria in terms of physiological factors. After all, in patients, one part of the body completely lost sensitivity, and the areas adjacent to them continued to feel various stimuli. In addition, before Freud created the theory of “I,” “Id,” and “Super-Ego,” it was impossible to explain the behavior of people that took place in a state of hypnosis. That is why the scientist suggested that only part of the processes occurring in the psyche is a reaction of the central nervous system.

Consciousness and Unconscious

The division of the psyche into conscious and unconscious is the basic premise of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud

Consciousness is not the basis of the psyche, but only a part of it. Why can’t we say that the conscious is the psyche? Here is the simple explanation Freud gives.

It is impossible to keep anything in consciousness for a long time. A mental element (for example, an idea), which is present in consciousness at a given moment, after some time gives way to other mental elements. However, under certain, easily achievable conditions, this idea can appear in consciousness again, and not because of a new perception, which led to the awareness of this idea for the first time, but thanks to memory [2].

Let's explain with an example

So you spent the whole morning walking through the forest and picking mushrooms. Having returned, you have already forgotten about the forest, your mind is busy with other things that were planned for that day. But then the day is over, you go to bed, and as soon as you close your eyes, a picture of nature, the forest you walked through, and the mushrooms you picked, emerges in your mind.

Thus, all the time while other mental processes were occurring in our consciousness, the previously conscious idea was outside consciousness, that is, it was unconscious. This is the unconscious, which, according to Freud, is the latent unconscious (preconscious). In addition, he also highlights the repressed unconscious. Unlike the first, this unconscious is formed through the process of repression, the essence of which is to prevent the idea from reaching consciousness.

The difference between these two unconscious, which Freud identifies, is described in most detail in his work “Delusions and Dreams in “Gradiva” by W. Jensen.”

Everything repressed is unconscious; but we cannot assert with regard to the entire unconscious that it is repressed. … “Unconscious” is a purely descriptive, in some respects vague, so to speak, static term; “repressed” is a dynamic word that takes into account the play of mental forces and indicates that there is a desire to manifest all mental influences, among them the desire to become conscious, but there is also an opposite force, resistance, capable of holding back some of such mental actions, among them awareness action. The sign of the repressed remains that, despite its power, it is not capable of becoming conscious. Sigmund Freud

In the process of further psychoanalytic work, it turned out that these divisions were not enough, and then Freud identified three components of the psyche: “It”, “I” and “Super-ego”.

Preconscious

This area is sometimes called available memory. It includes all human experience that is not currently used by the individual. Nevertheless, the necessary information can always easily return to consciousness. This happens either spontaneously or as a result of small efforts.

By preconscious, in his theory of the “I”, “It” and “Super-Ego”, Freud understood the part of the psyche that, according to its description, is unconscious. However, when a person directs attention to it, this area becomes potentially conscious. The sphere of the preconscious, in particular, includes free associations, which are used by specialists in the practice of psychoanalysis.

"It", "I" and "Super-ego"

“It” represents a completely unconscious part of the psyche, in which all the repressed drives of the individual remain. This is an unknown, inaccessible part of the personality, in which there are no moral guidelines, moral assessments, concepts of good and evil.

“It” is what is the basis of the personality of any child. They are driven by primary biological needs, desires, and emotions. Therefore, children, especially under the age of 5-6 years, are mostly selfish and capricious. Over time, the child learns from the parents what is right and what is wrong. His system of values, norms, and rules of behavior is formed. Already at school, the child learns to interact with other people, to observe religious, moral and legal norms in force in society. It is the influence of parents and the social sphere of society that determines the formation of the “Super-I”.

The "super-ego" is the suppressive element. Being the complete opposite of the “It,” the “Super-Ego” personifies conscience, ideals, social norms and everything that limits the individual, makes him civilized and allows him to live in human society.

By its nature, the “Super-Ego” is closer to the “It” than to the “I”, simply because it is also unconscious, only unlike the “It”, which is a kind of hereditary, the “Super-Ego” is an acquired unconscious [7 ].

Both the “It” and the “Super-Ego” manifest themselves through the third psychic authority - the “I”.

“I” is already the sphere of consciousness. It acts as an intermediary between the “It” and the “Super-Ego”.

The functional importance of the “I” is expressed in the fact that in normal cases it has access to mobility. In its relation to “It” it is like a rider who must bridle a horse that is superior to him in strength; the difference is that the rider tries to do it with his own strength, and the “I” tries to do it with borrowed strength. If the rider does not want to part with the horse, then he has no choice but to lead the horse where the horse wants; so the “I” transforms the will of the “It” into action, as if it were its own will. Sigmund Freud

Thus, personifying common sense and prudence, it controls the mental processes occurring in the mind.

But because of its role, the “I” is constantly under pressure from both the “It” and the “Super-Ego”.

Extreme influence of any of them leads to negative consequences. For example, in the case when a child is brought up in strictness, is constantly punished and made to feel guilty for his behavior, gradually the pressure of the parents is replaced by the pressure of the “Super-I”. Punishment from without is replaced by punishment from within. As an adult, such a person often becomes depressed, feels guilty, and experiences pangs of conscience. At the same time, the “Super-Ego” becomes so tyrannical that a person blames himself not just for past actions, which he considers unworthy, but even for unworthy thoughts. Thus, the guilt and reproaches of such a person’s conscience are often caused not by an objective assessment of his actions, but by the person’s formed idea that he deserves it, that he is guilty, etc.

There are even more examples of what happens to people in whom “It” has the greatest influence. There is no need to talk about people who ignore social values, break rules and do not consider the feelings of others.

Thus, an imbalance between the three main components of the psyche brings suffering to the individual, and sometimes leads to mental disorders and the emergence of neuroses. “I” is trying to prevent this. And the main method is the process of displacement.

"Super-ego"

“Super-I” (Superego) is such an attachment to the “I” (ego) - a “branch” of global public morality in the head of an individual. It arises at the later stages of personality maturation on the basis of a more or less formed “I”.

The “super-ego” consists of beliefs that suppress the “id” about what is “should” and “correctly”. Thus, the momentary animal desires of the “It” come into conflict with the ideals of the “Super-I”.

The first rudiments of self-control in a child are a sign of the emerging “Super-I”. I believe that it is useless to hope to raise an enlightened offspring. Apparently, going through complexes and neuroses is an inevitable stage of mental maturation.

The “super-ego” grows on the basis of parental punishment (for disobedience) and encouragement (for obedience). This is how a feeling of guilt and pride arises in us. We learn to feel guilt for the lack of control of our “Id” and pride for conforming to the ideals of the “Super-I”.

This is roughly where all the problems of self-importance and self-doubt root. This is our eternal fear of screwing up, the constant race for “the best” and the endless assertion of our place in life.

The “super-ego” with its demands is insatiable, because it is not a reservoir, filling which you can calm down, but a non-stop working mechanism that sucks out personal strength. It encourages us to endlessly recheck the reality that is happening out of fear of possible guilt and in the hope of encouraging pride.

The “super-ego”, by its own local standards, forces one to realize an ideal life. The noblest of our society are particularly drawn to his ideals. Illustrative examples can be found in Russian classical literature - there are many of them in almost any novel.

The “super-ego” creates for us good and bad, good and sinful. Depending on the worldview, the “Super-Ego” can paint itself in the images of the divine and sublime, and “It” can dress itself in the veils of the demonic and ignorant. From this perspective, all the darkness of the outside world is just a projection of our own suppressed animal nature.

The “I” (Ego) in this connection rushes about in search of a reconciling compromise between the “It” and the “Super-I”. The “I” plans and postpones, observes rules and rituals, disguising animal desires with a pious mask. That is, we fight for honor, suppress, disguise or embody the primitive habits of the “It” in a decent, digestible form in order to catch bonuses from the “Super-I” (Superego).

crowding out

The doctrine of repression is the foundation on which the entire edifice of psychoanalysis rests, ... Sigmund Freud

Repression is one of the key concepts in psychoanalysis, denoting the process as a result of which the “I” retains drives, thoughts, and aspirations in the unconscious, preventing them from becoming conscious.

The process of repression occurs when attraction for some reason is unacceptable to the individual. Satisfying this drive would definitely cause pleasure, but at the same time an unpleasant feeling, in the form of guilt, disgust, etc. This is due to the fact that this drive, for some reason, is not approved by the person and does not fit into his picture of the world.

And at first glance, it seems that by repressing the attraction, we get rid of it, but in reality it continues to exist in the unconscious. Repressed drives held outside consciousness are the source of various neuroses for the simple reason that the repressed produces continuous pressure in the direction of consciousness, and therefore the same constant reciprocal pressure has to be exerted on the repressed in order to continue to keep it in the unconscious. This confrontation requires constant concentration. However, the desire can change, give rise to other states and processes, which, despite constant repression, can penetrate into consciousness.

This leads us to the conclusion that the process of repression is a necessary protective mechanism that ensures the relative constancy of the psychological system of each individual.

"Super-ego" or "super-ego"

Superego is a kind of superstructure over consciousness, which is formed during a person’s life under the influence of social norms, requirements, prohibitions - taboos. On the one hand, the “superego” allows us to distinguish between good and evil, good and bad, and to be aware of moral principles and ideals. But on the other hand, according to Freud, the “super-ego” limits a person’s freedom, driving him into the framework of generally accepted norms. Moral prohibitions prevent the satisfaction of natural needs and the manifestation of equally natural aggressiveness. This leads to various mental problems, such as neuroses.

To avoid a critical situation, a person’s consciousness, his “I”, invents various methods of compensation or sublimation - transforming the energy of forbidden desires into something more acceptable to society.

Instead of output

The ideas discussed above help to understand the essence of psychoanalysis and its role in the development of psychology. And despite the fact that at present, psychoanalysis is not as popular as before and is often criticized, it cannot be denied that it has influenced the entire Western culture. No other direction in psychology has gained such popularity as psychoanalysis has gained. Initially created as a method of diagnosing and treating hysteria, it became a general philosophical doctrine that attempted to explain the structure of the human psyche, to determine the essence and significance of the deep and unexplored psychological processes of the unconscious.

"Ego" - "I"

To denote the level of consciousness in psychoanalysis, the Latin concept ego is used - “I”. If the “id” is the animal nature, then the “ego” is the rational part of the psyche. These are all things that we are aware of, that we can manage and meaningfully regulate. Strange as it may seem at first glance, the volume of the “ego” is not too large compared to the “id”; the sphere of the conscious is much smaller than the region of the unconscious.

Although S. Freud himself paid less attention to the analysis of this level, its functions are not difficult to determine. These include the following:

- assessment of the real situation;

- analysis of meaningful information received by consciousness from external and internal sources;

- making decisions;

- control over their implementation;

- partial understanding of desires and transforming them into actions or moving them to the level of the unconscious (displacement);

- rationalization (explanation) of actions and actions.

In fact, the “I” is a mediator in the struggle between the “it” and the “super-ego”. This level of the psyche is constantly looking for a compromise between natural needs and the demands of society.